“Consistency” certainly isn’t the most fitting word to describe my production on this blog. That’s especially true for this series of posts aimed at breaking down the direction and visual presentation of some of the shows I watch on a weekly basis. Starting with the fact that (as alluded to in my previous post) I finally decided to change its name to “Direction Notes”, just a little over a year since I started writing these pieces, and just a little under a year since I began calling them “Episode Notes”.

But this sort of rebranding happens all the time, doesn’t it? What’s far more important is that it’s been roughly 9 months since I published my last write-up about Shoushimin Series, specifically, about episodes #3 and #4. Believe me when I say that I still have all the notes, timestamps and screen-caps I took of (almost) every remaining episodes of the first cour, but for one reason or another, I ultimately never got around to putting them together into actual posts.

Fortunately, the episode that came out last Saturday, 6 weeks since the second cour started airing back in April, felt so strong and cathartic that I believe it’s the perfect opportunity to get back on track with this series, momentarily glossing over the episodes I skipped (in the hope I’ll manage to address them sometime in the future), and spending a few words directly on Episode #16, “Midsummer Night” —the climax of The Autumn-Exclusive Kuri Kinton Case Arc.

Episode 16 – 真夏の夜: Midsummer Night

Storyboard: Nobuyuki Takeuchi | Episode Direction: Shoshi Ishikawa

Before I start, I’d like to point out that, as usual, I won’t be covering or analyzing the content and themes at play in the episode; there’s who already has very skillfully written at length about those aspects, far more insightfully than I ever could.

Instead, what I’ll be doing is focusing primarily on the directorial aspects of the episode, the mise-en-scène and visual arrangement that brilliantly framed Honobu Yonezawa‘s story and brought to our screens all the intensity permeating through its climax.

The first impression I got from the very first scene of the episode was how dark everything looked, or rather, how stark the contrast between the background and the lit-up elements felt. To put it yet another way, the emphasis on lighting is something the episode outlines and insists on from the very first shot we’re presented with.

Light, especially its color, and even more-so its source, is indeed the main visual theme throughout the entire runtime of the episode, playing a central role in more than just one way.

What this suggests, on a broader outlook on the approach this episode takes on the mandatory taste of visual storytelling ever-present in this show, is a strong focus on crafting the perfect ambience to keep the viewer engaged, almost luring us in, allowing its subtleties to be conveyed in a more passive and engulfing way.

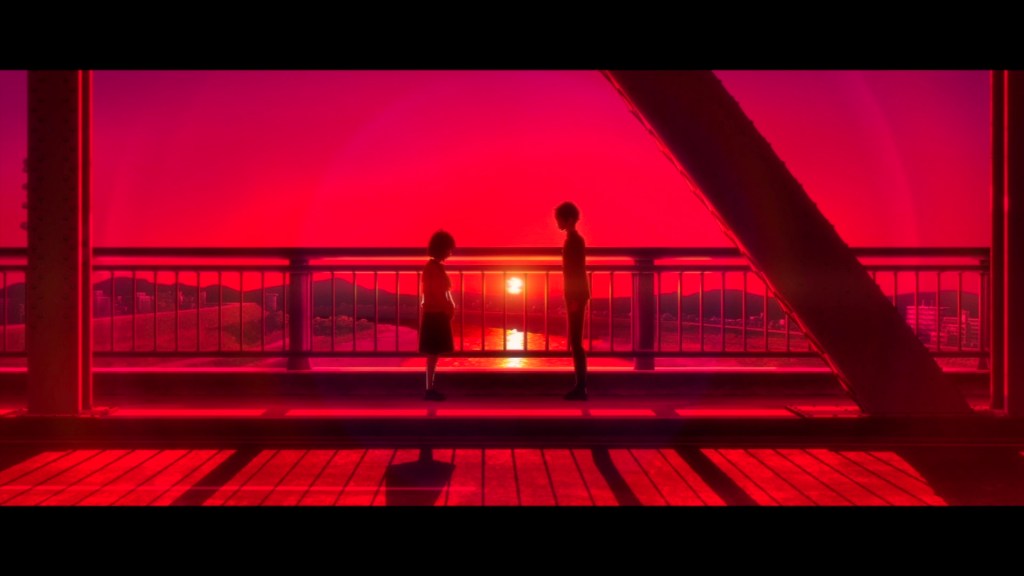

After the brief introduction featuring a conversation as important as it is short between Kobato and Kengo, we’re welcomed by an alarming yet somewhat comfortingly beautiful red palette. This serves as the stage for a highly anticipated reunion: the one of Kobato and Osanai —the fox and the wolf— and what better setting than the warm light of a raging fire, set by the unidentified serial arsonist on the loose? Yet, despite the unnerving tone of situation and the imminent threat of some fuel tanks potentially catching on fire and exploding (the framing of which doesn’t fail to subtly embed a sense of powerlessness and tease another visual theme that’ll play a major role later in the episode), the sequence is filled with an inexplicable feeling of delight and lightheartedness, if anything, remarking once and for all that there’s absolutely nothing ordinary about our main duo and their relationship.

Much like a moth lured in by lightbulbs, with all his vehemence Urino reaches Kobato and Osanai following the light from the fire, and after a very brief and inconclusive confrontation, our inexperienced make-believe detective runs after the fleeting Osanai —one could say, majestically falling for her trap.

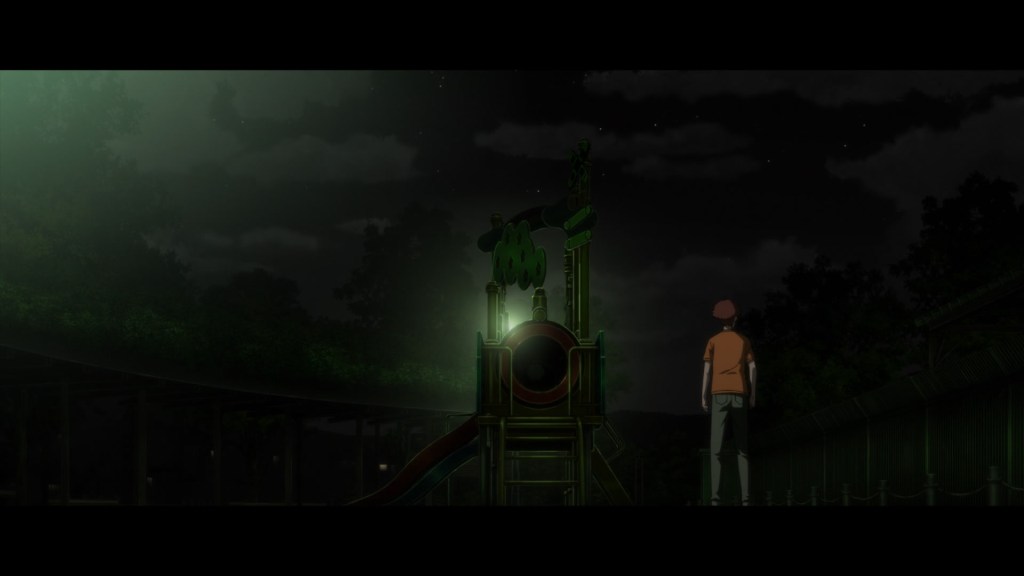

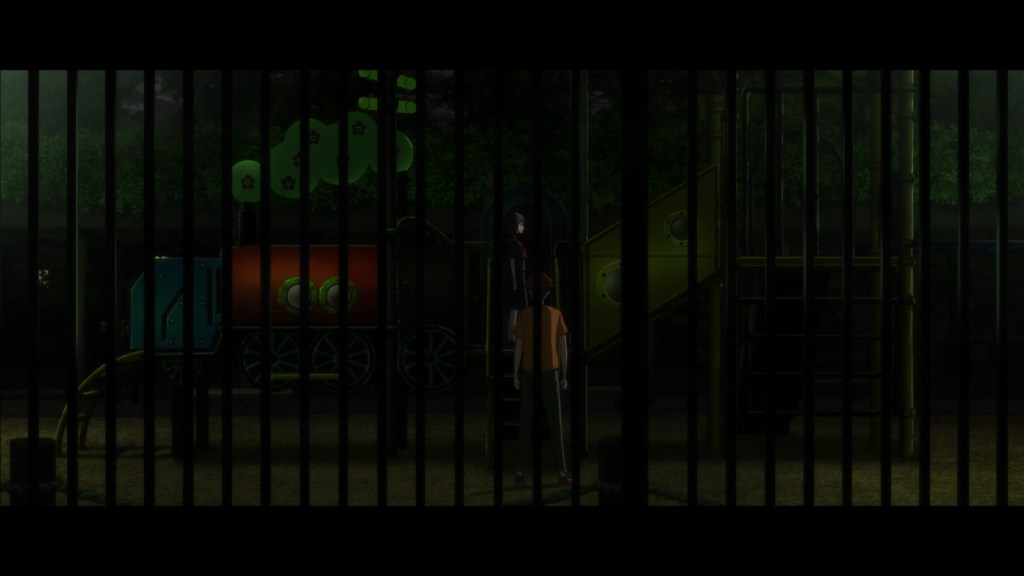

The location changes to an eerie public park, lit-up only by the dim light of a streetlamp enveloping everything in a poignant and ominous green tint.

As Frames 5 to 7 suggest, that of confinement is the main visual theme of this next sequence; Urino, having been successfully lured into the wolf’s den, is as far as he can possibly be from a position of control, despite him supposedly being the one who cornered the culprit.

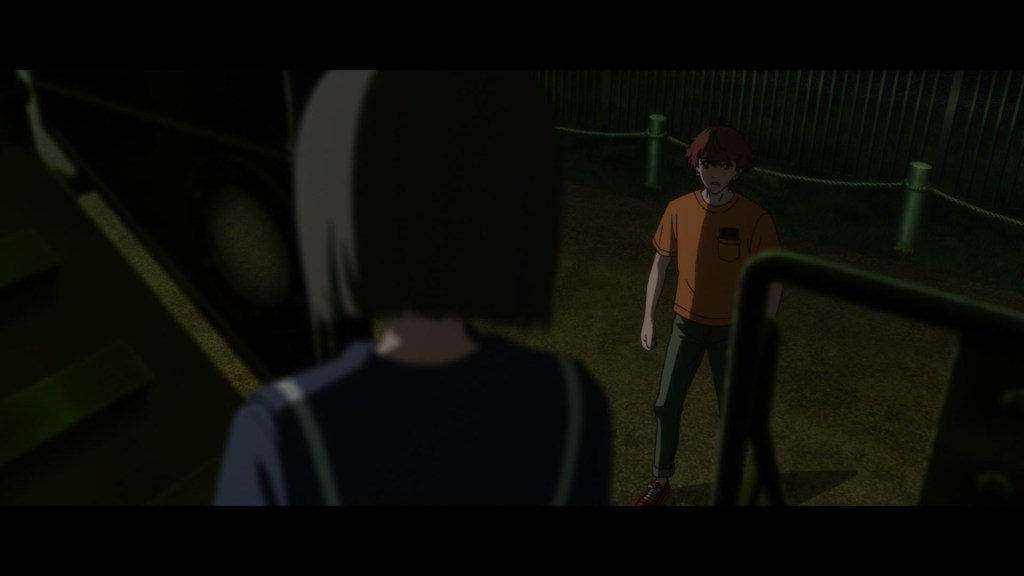

This idea of Urino being the one who’s actually trapped is rendered very explicitly, with the foreground layer literally depicting a stretch of imposing fences, trapping him from many different angles. At the same time, the same concept is also conveyed in a more intrinsic way, via a very telling use of spacing within the frame, paired with a focal shift effect at the end, leaving him little to no room to breathe.

If it wasn’t already clear enough, another deliberate choice that establishes Osanai‘s presence as the one in control of the situation, is the very physical detail that she, until the end of their confrontation, is always positioned above Urino, the latter forced to constantly raise his gaze in order to meet hers, who’s always looking downwards. Furthermore, Osanai is the only one that gets to move around freely in this environment, while Urino stands still in the same spot almost all the time —after all, it’s her den, not his.

In another unconcealed symbolism, the direction cleverly indulges in a particular framing of the lamp, shot from below much like Osanai during the entire sequence, where increasingly many bugs are lured in by the lightbulb. The cold and dim light emanated from the lamp serves as an obvious metaphor for our small (in size, but certainly not in ego) girl and her pale warmth towards the School Newspaper Club President, while the moths represent of course Urino, and his mis-directed deductions.

As clouds partially obscure the moon, lost but confident in the middle of the night, he ends up clinging to an artificial and contrived source of light, unable to see —let alone reach— the far away truth his own ambitions set out to unveil.

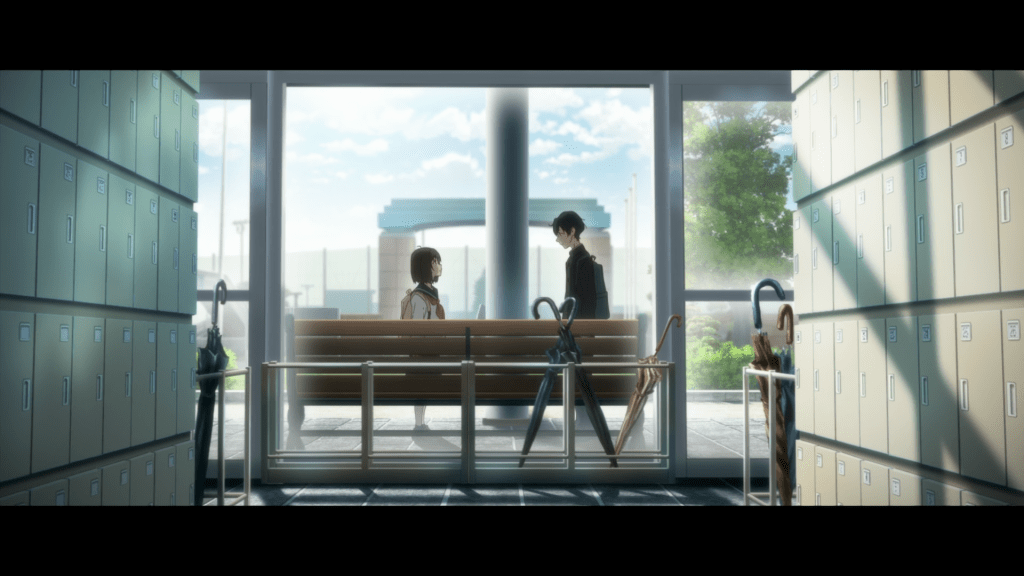

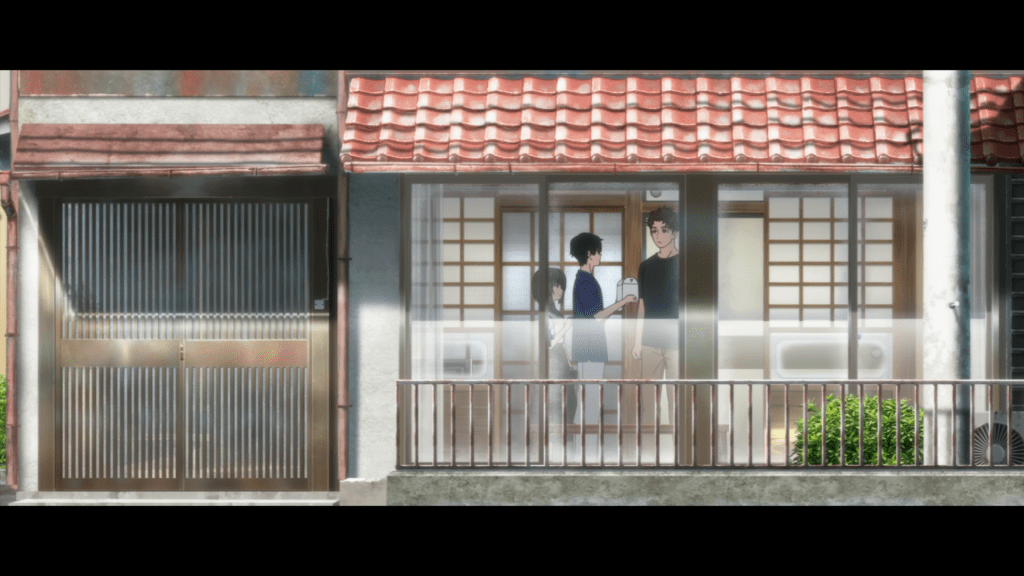

Even in the confidence of his flashbacks, the framing leaves no room for doubts in conveying Urino‘s flawed approach. His impulsive and overzealous personality isn’t exactly fit for the role he appointed himself to play, as neither back then nor now his figure is able to break out of the very narrow perspective, outlined by the window’s frame, that he confined himself into by failing to even consider taking a broader look at the situation before drawing the conclusions.

I haven’t mentioned it yet, but an unnerving feeling of tension unsurprisingly lingers throughout the whole sequence, which lasts for about 3/4 of the entire 23 minutes runtime of the episode. Contributing in making this sensation feel even more palpable, is a subtle matter of rhythm. While Urino and Osanai are having their conversation, the former’s lines are often visually cut in half; in other words, the camera erratically changes position or angle while he still isn’t done talking. It’s jarring, deliberately so, since it’s something that rarely happens under normal circumstances. Here though, it’s a very tastefully employed trick to make his assertions feel questionable and hesitant before he’s even given the chance to fully articulate them.

Speaking of dialogues, I cannot fail to mention the incredible performance by Hina Youmiya, Osanai‘s voice actress, reaffirming hers as one of the best castings in recent times. Her whispery tone seems to come directly from the character’s lips, precisely controlling the many emotions she’s feeling during the sequence, whether it’s fervid excitement, utter disappointment, or both.

In the final phase of the episode, when Osanai reveals the last and definitive piece of the puzzle to the poor Urino, the camera trembles like it never did before; his self-confidence shatters and the lingering feeling of uneasiness coalesces in a cathartic sense of impotence. The visual verticality of the scene is once again crucial to its presentation, as Urino raises his gaze even higher, and finally gets a proper, humiliating glance at the moon, which too is looking down at him, now clear of any obstacle.

Defeated, the ill-fated prey runs away, while Osanai is juxtaposed with the very same streetlamp from before —this time, with no bugs flying around its light anymore.

Emerging from the depth of the wolf’s den, there’s Kobato, who naturally finds himself at home there, and has been patiently waiting for this sophisticated hunt to reach its end.

In all honesty, as soon as this second cour of Shoushimin Series started airing I was already sure I would end up writing at least one blogpost about it. It’s been quite a while now, so whether or not this short piece meets the quality standards of my previous posts on the show, I leave up to you to decide. Nonetheless, I hope I was able to provide some interesting insights on this shows’ ever so resourceful direction, that you may (or may not) have missed while watching through the episode.

I had a lot of fun putting this write-up together today, but I don’t plan on making a return to a regular publishing schedule any time soon. That being said, if the opportunity arises again for another sporadic post like this one, I might find myself back at the keyboard sooner than expected…