On January 11, just a handful of days before Season 2 started airing, one final PV came out, and amidst the sense of excitement and sheer joy that this sequence of mesmerizing visuals left me with, I realized I had never stopped to think about what it is that makes Frieren look and feel so unique.

It’s been roughly two years since Season 1 ended, and all it took was a mere 80 seconds of montage to sharply evoke that very defined—yet hard to describe—set of sensations that finally, “Frieren is back!”.

Today, 29 years and roughly 3 days after the death of Himmel the Hero, we’ll be adventuring through the first episode of this long awaited return, in the pursuit of laying down a decent-enough outlook on Frieren‘s distinctive taste and idiosyncrasies.

While not much has changed in the grand scheme of things compared to season one, this second season of everyone’s favorite elderly elf anime came back with a major internal shift in terms of position of the creatives involved in its production.

Essentially all of the core staff members, including the Scriptwriter, Art Director and Color Coordinator, as well as many Episode Directors and Animators, are still (figuratively) sitting at the same desks as two years ago, but the person in charge of coordinating the collective work of this talented crew, as well as defining the overall creative vision for the project, is no longer the man who goes by the name of Keiichiro Saito. Instead, while it might not be groundbreaking news to anyone at this point, Sousou no Frieren‘s second season’s Director is none other than Tomoya Kitagawa, who had previously covered the role of Chief Episode Director for the second cour of the first season (episodes 17 to 28), carrying out several storyboarding and directorial duties.

This significant change wasn’t something forced or imposed by any sort of sinister circumstance; rather, it was actually Saito‘s own intentional decision to step back from a more hands-on position to a more supportive and assistive one, that eventually get credited under the name of “Direction Cooperation”. Now, I don’t wanna delve into what that means practically, as the man himself answered this exact question in a recent interview. Instead, I want to take this as an opportunity to identify and discuss what I believe are Frieren‘s intrinsic strengths, and how this first episode of Season 2—unsurprisingly storyboarded and directed by Series Director Kitagawa himself—proved to have fully understood them and carried them over into this continuation of our party’s laid-back journey to Ende.

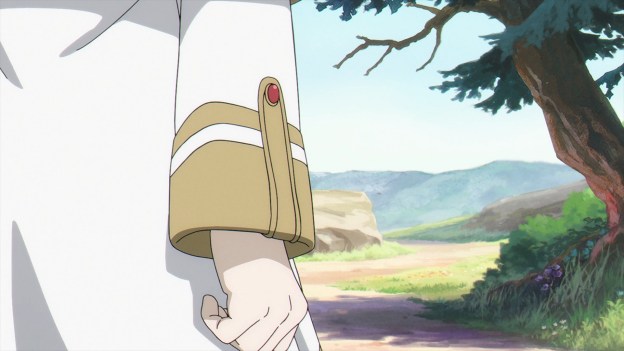

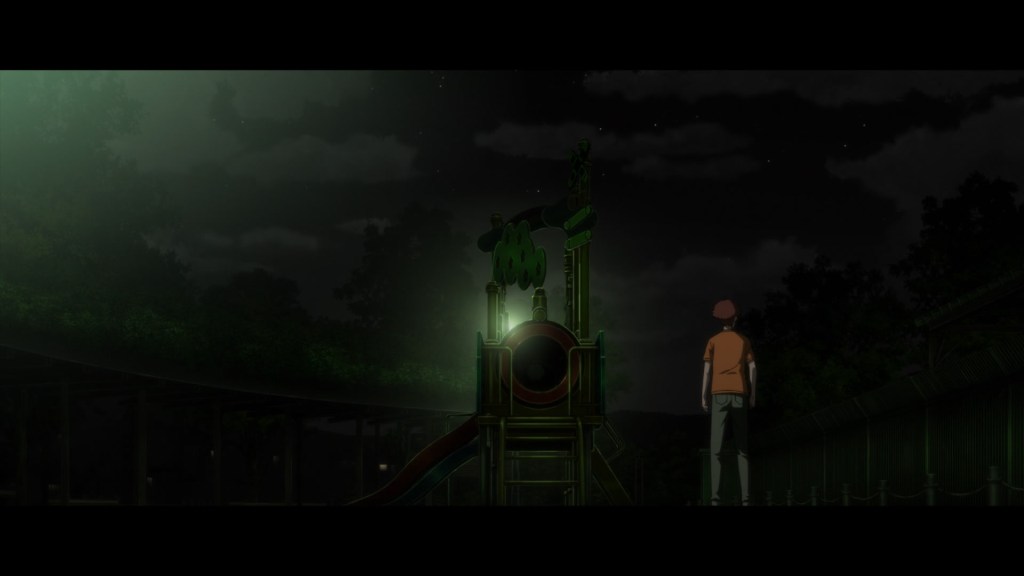

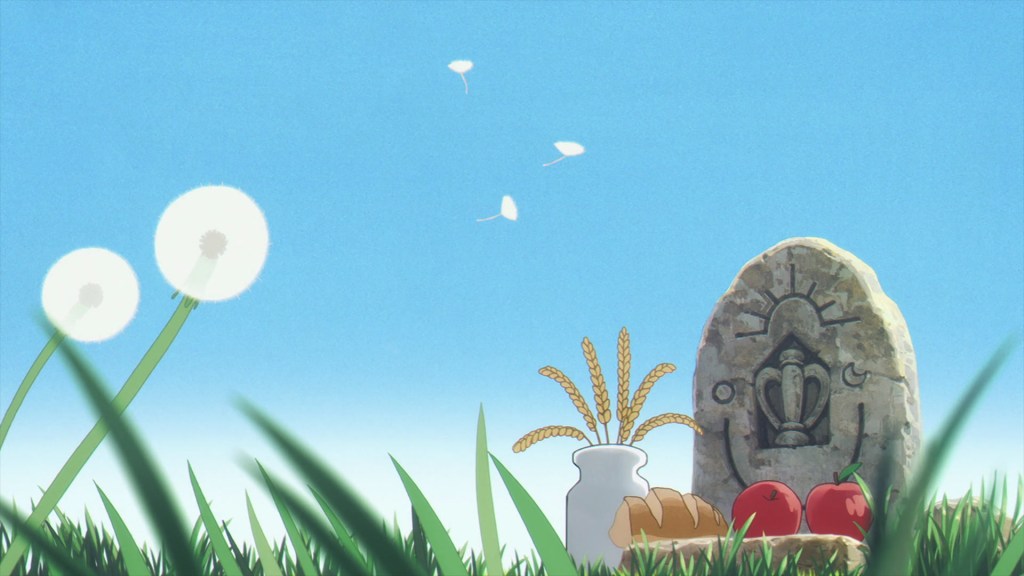

Right as the episode started playing, you get instantly overwhelmed by a strong sense of familiarity. For starters, that’s likely because the anime-original opening sequence directly mirrors the very first few cuts of season one’s first episode, this time featuring Fern and Stark by Frieren’s side, instead of the legendary Hero’s party. On a second analysis, you can’t help but feel the nostalgic warmth of Harue Oono‘s soothing & calming color design, that paired with the mesmerizing background art, plays a huge role in making the visuals feel vividly intimate.

The emphasis on natural landscape is one of Frieren‘s key ingredients that undoubtedly make up part of its identity, as Kitagawa pointed out in the aforementioned interview, and these familiar artistic choices, going all the way down to the Photography department, set up the perfect environment to make us feel the connection with seasons one, almost as if time never passed between them.

Things like the peculiar grainy filter are direct visual cues that help unmistakably recognize the specific taste that defines Frieren‘s imagery. Another example of this, are the very spacious and minimal compositions, where the background elements dilute into nothing but the very distinctive sky gradients, granting more room for the shots to breathe, and briefly aligning the visual space of the frame with the tide-like openness of the tempo.

The thoughtful sense of rhythm that permeates every sequence and modulates its pacing, is definitely another major player in establishing the show’s core identity. The contemplative nature of Frieren‘s direction was a distinctive trait of season one, and served as a very deliberate tool to control the flow of information on the screen, allowing the eye of the viewer to rest on specific shots, or redirecting the focus on specific portions of the frame.

The total and careful control over every visual aspect of the production, showcased at virtually any given moment throughout the episode, is what struck me the most while watching the premiere of season two. Maintaining such a high level of intentionality in the way the scenes are staged across the episode’s entire runtime is definitely not something you see often in TV anime.

Kitagawa and his team—following Saito‘s experienced guidance—have been confidently building upon the incredibly solid foundation they consolidated throughout the previous 28 episodes. Their remarkable ability to make the most out of the fundamental building blocks of anime, synchronizing all of them under the sharp and essential vision they all believe in, is what ultimately makes Frieren feel so strongly coherent and uniform on the screen. In an way that’s almost meta, this fits really nicely with the story’s themes, when you consider the core principles that set Frieren’s and Fern’s magic style apart from other mages: an outstandingly solid & diligent approach to the very fundamentals of their craft.

Practically speaking, this overarching control is mainly exemplified through the harmonious mise-en-scène, which (as I briefly anticipated earlier) excels at its thoughtful use of space. When I say that the staging is always very deliberate, I mean that the shot compositions are consistently curated to convey a subtle sense of balance (or imbalance, depending on the need) within the main narrative context of this season, which, as Kitagawa made very clear, is our ever-so-goofy trio of main characters and their growing chemistry.

“Balance” is indeed a central theme of this first episode, and a necessary one to prepare the ground for the adventures that Frieren’s party will be going through over the course of the next nine weeks.

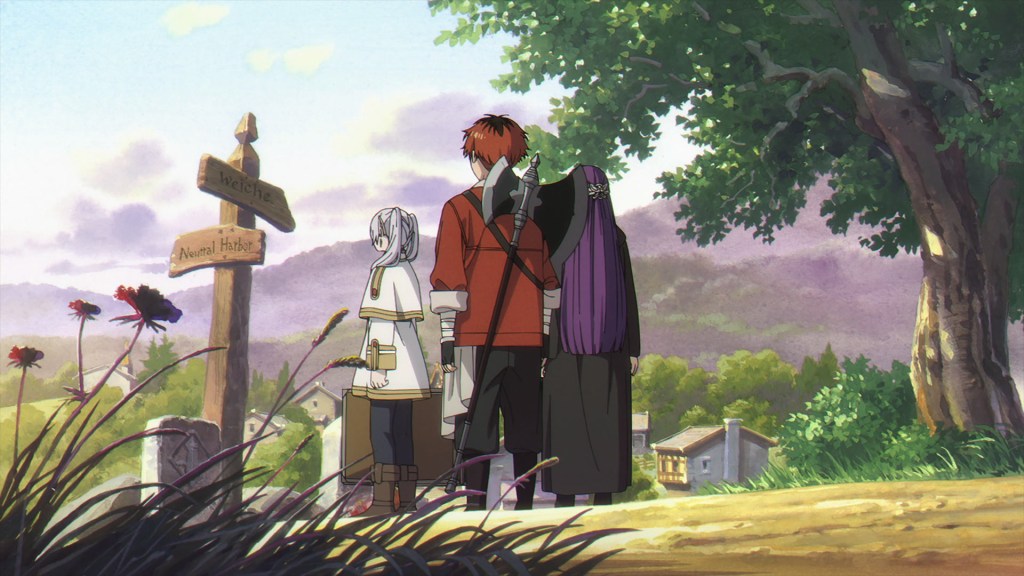

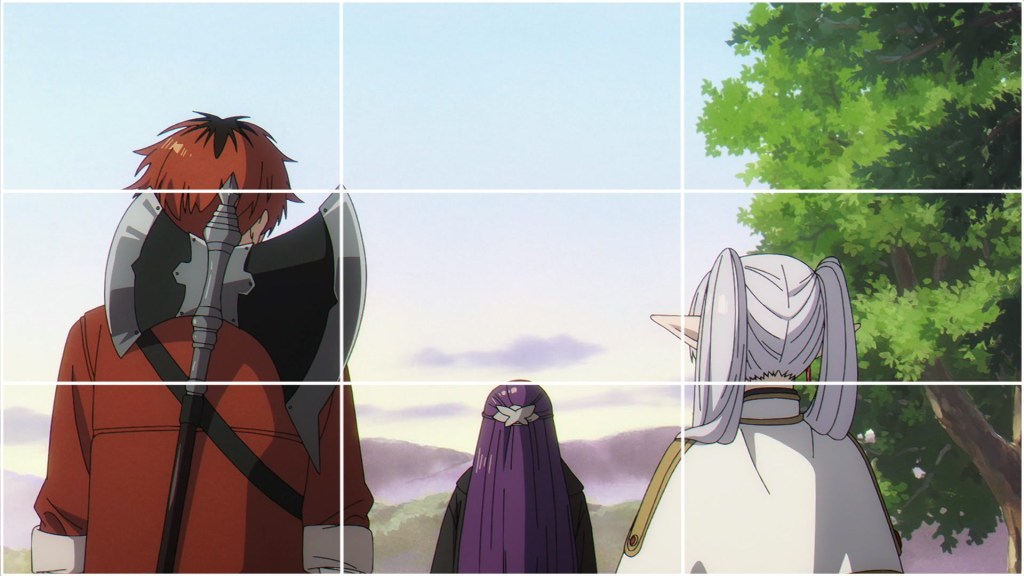

Visually, it’s the clever use of compositions that equally distribute the density of the elements in the frame into neatly separated sections, that bakes this perception of balance directly into the geometry of the screen.

While also offering cues about the depth of the shot, this precisely three by three sectioning of the screen works almost too perfectly as a visual blueprint to frame Frieren, Fern and Stark as they leisurely find their own space within the party.

Each one of them almost always takes up exactly one third of the screen, uniformly distributing the tension across the frame, and making the cuts feel more comfortable and straightforward to follow, as the eyes of the viewers are imperceptibly drawn towards the center of the screen.

This framing also helps in conveying figurative distance between the characters, by creating invisible barriers that limit their individual scope of action.

“Alignment” is also a huge visual theme frequently featured in the show, and this episode is certainly no exception to it. Used as either an explicit connection between the past and the present, or a way of stitching together consecutive sequences, parallels always carry a lot of meaning in the visual language of Frieren.

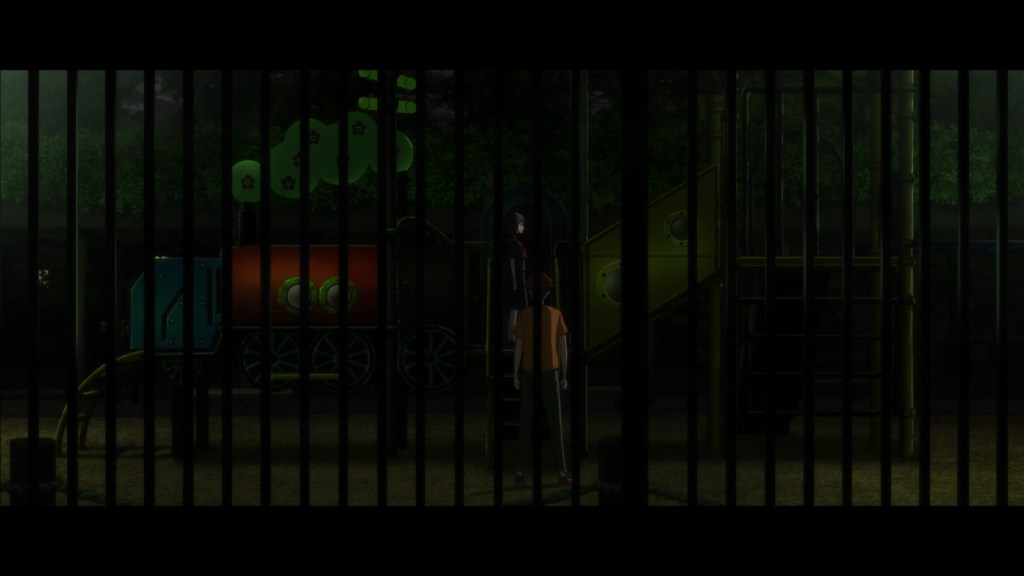

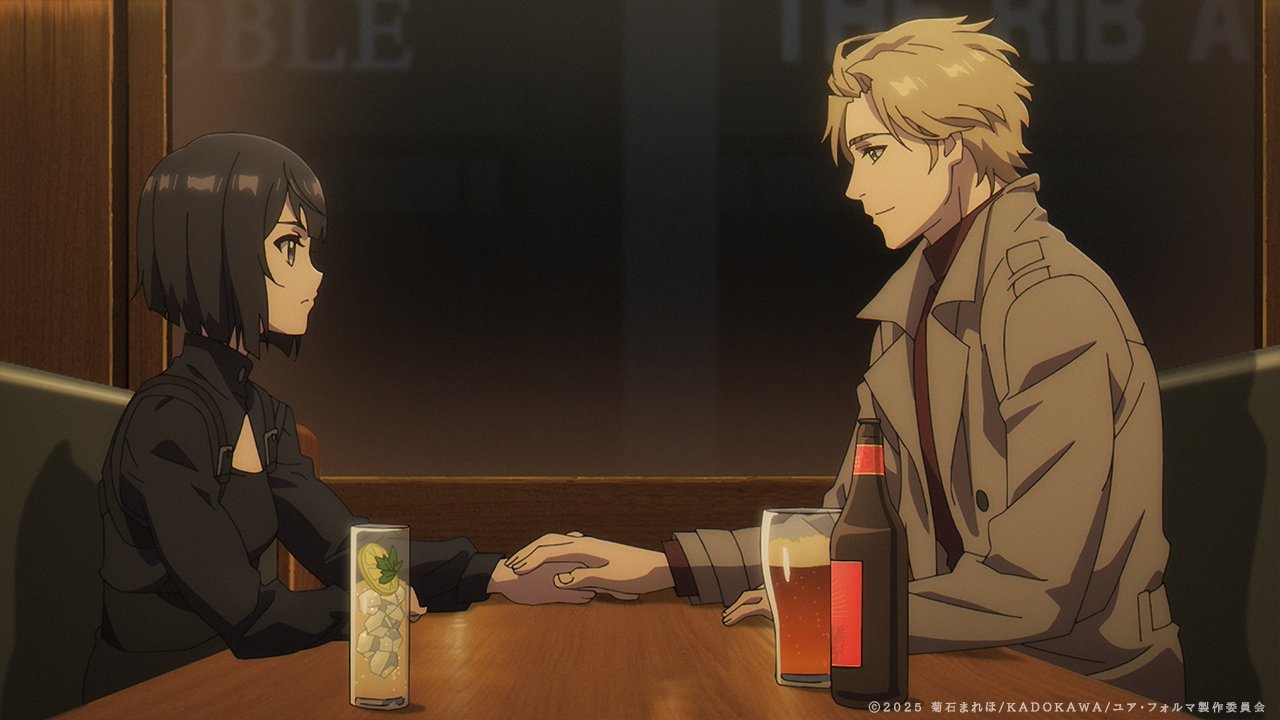

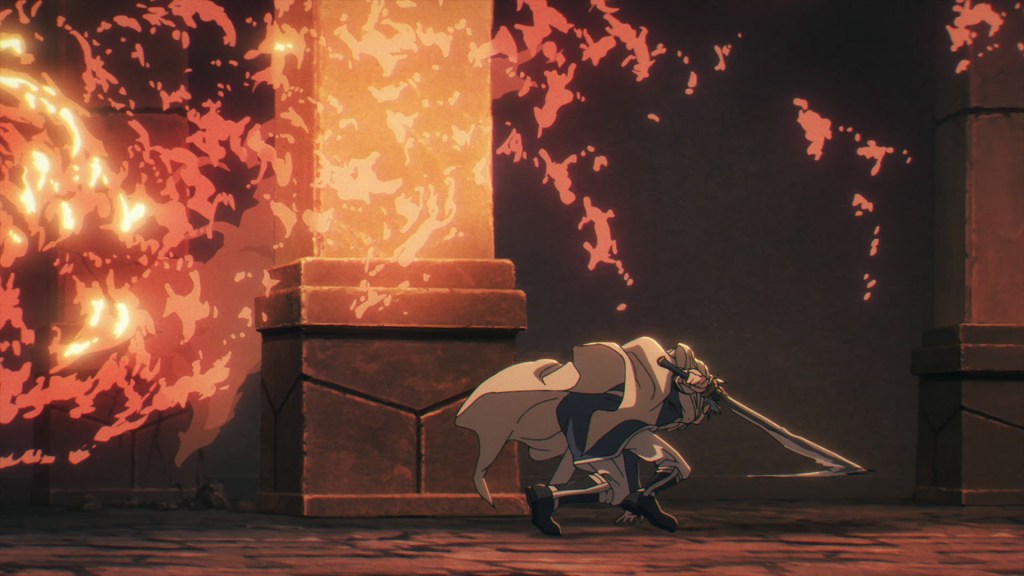

A specific scene of this episode, where Stark and Fern have a brief chat to clear up the First Class Mage’s doubts on the Warrior’s attachment the the party, represents a remarkably well executed example of this theme. Combined with a striking tonal contrast of warm and cold tints intrinsically creating distance between the two of them, the use contrasting but very much parallel shots of the same object—the lantern—perfectly mirrors the narrative of them finding a renewed alignment, by at first placing the prop disproportionately to the right side of the frame, and later exactly at its center.

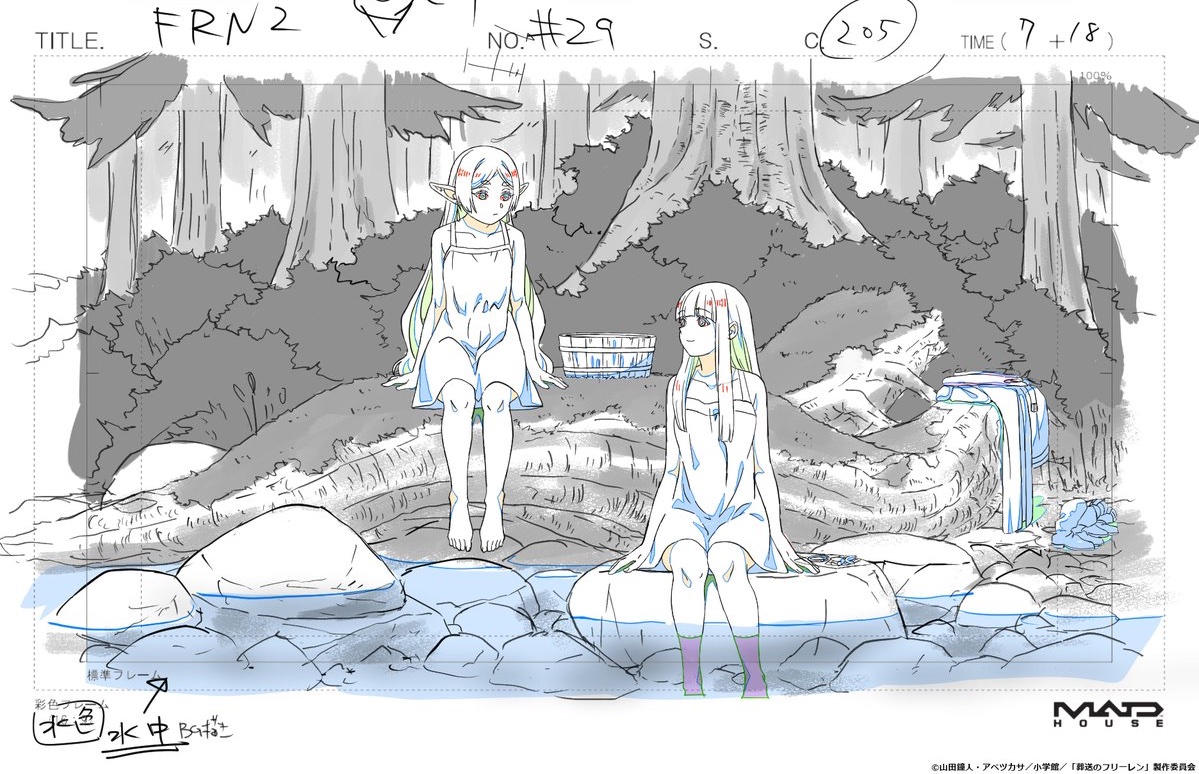

The other kind of parallels this show makes conspicuous use of, is the juxtaposition of Frieren’s flashbacks with the present. It might seem like an over-used and perhaps even low-effort expedient, but given how pivotal of a theme the passage of time is to the story, it really contributes in making the transitions feel much more memorable, and in a sense, more weighty too.

As the story shifts its focus toward the growth of the current party, it’s a nice touch to see Frieren proactively drawing the connections between their present journey and Himmel’s party’s, rather than those memories simply occurring to her by coincidence. Maybe she’s really starting to grow more empathetic toward others…

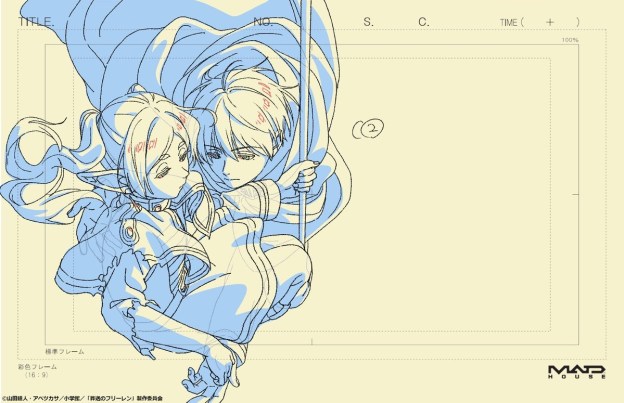

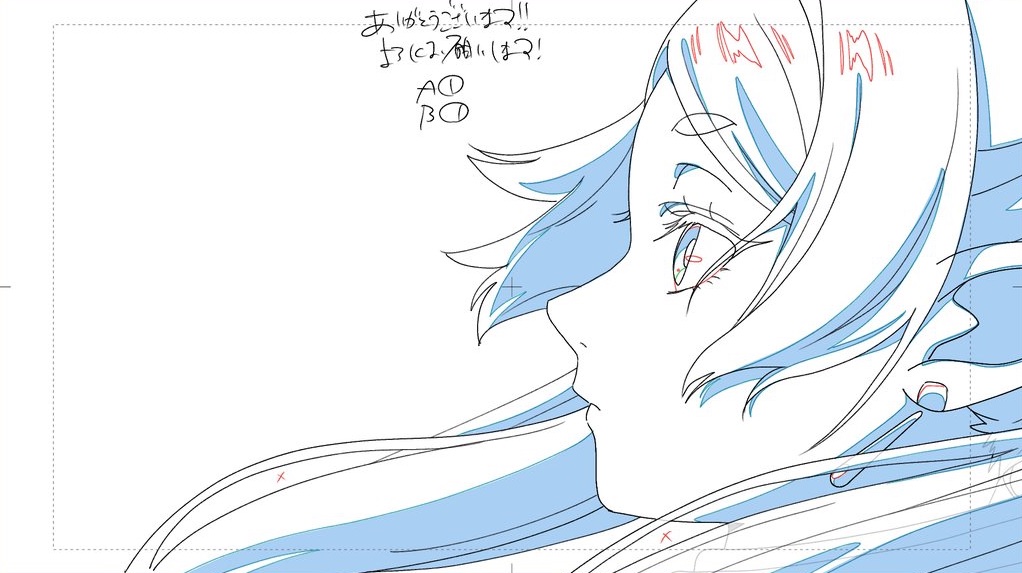

As a closing note, it would be impossible to talk about this premiere without mentioning the stunning bits of animation by Kouta Mori, as well as the amazingly soft character acting towards the end of the episode. Another key to aforementioned consistency are without any doubt the blissfully many corrections by the solo Animation Director, Takasemaru (a.k.a. Akiko Takase).

As Saito recently said, this ideally balanced mixture of action, tender & lyrical sequences, and genuine comedy that comes across as natural, is one of the major reasons behind Frieren‘s immense success.

To be honest, I didn’t expect to write this all in one go. Instead, I started writing this with the idea of drafting a cumulative post, one that would cover more than just a single episode like I usually do on this blog. However, as I kept fleshing out my condensed thoughts after re-watching the episode, I realized it might have been better to have this piece come out as a single, separate instance to celebrate Frieren‘s return.

I probably say this a lot over here, but very few things get me excited in the same capacity as Frieren, and I hope I was able to make at least a tiny bit of its greatness transpire through my words.

Hopefully, throughout the next few weeks, I’ll manage to find the time and words to once again write about the chronicles of my favorite silly elf. Until then…