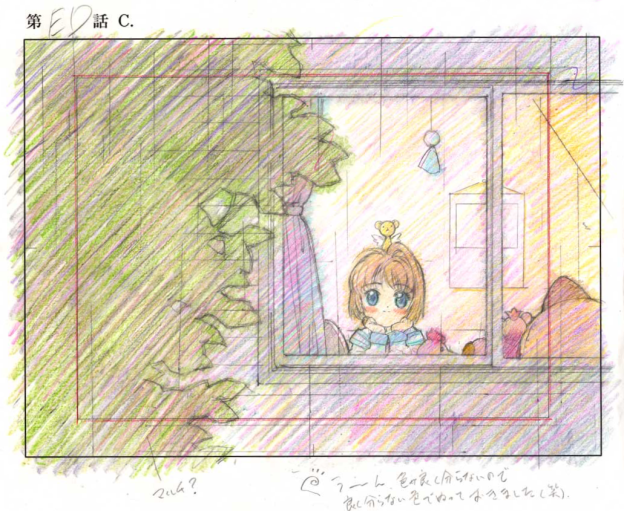

Original interview from Cocotame, published in two parts, Part 1 and Part 2, on October 21st 2024, original title: “TV Anime「Natsume Yuujinchou」Season 7 Starts Airing ― Chief Director Omori reflects on the 6,000 days spent together”, original interviewer: Hidekuni Shida; genga from Natsume Yuujinchou Shichi Episode 2, from Studio Shuka’s official Twitter account.

Part ①

“Natsume Yuujinchou” is a manga series by Midorikawa Yuki, first published in 2003 and still beloved to this day. The anime adaptation began airing its first season in 2008, and since then, a total of 80 episodes (including special OVAs) and a feature film have been produced.

What kind of feelings has Chief Director Takahiro Omori poured into this work, having been involved as both the director and chief director of the anime series? He shares the appeal of the seventh season, which started airing on October 7 (2024), and his passion for creating this work.

※ this interview was conducted on September 11, 2024.

~ Looking back at the origin of the beloved 16-year-long series ~

—— The TV anime Natsume Yuujinchou Shichi (Season 7) starts airing on October 7, 2024. Counting from the first season (which started airing on July 8, 2008), it has become a long-running series that has lasted a remarkable 16 years. Chief Director Omori, what do you think is the reason Natsume Yuujinchou has been loved all this time?

The anime Natsume Yuujinchou has a very easy-to-follow structure, as each story is fundamentally concluded within one episode. Furthermore, as you continue watching you begin to notice a larger, overarching story, and even with all the episodes released so far, there are still some mysteries left unresolved. I believe those elements are part of the reason why many people have been able to enjoy it for such a long time.

However, while it’s indeed a long-running series, there’s been a gap of around 7 years since the last broadcast [Natsume Yuujinchou Roku, the 6th season, began airing on April 12, 2017, and ended on June 21 of the same year], so out of the 16 years, it feels like half of that time has been spent on hiatus.

—— I’d like you to look back at 16 years ago. Do you remember when the proposal to adapt Natsume Yuujinchou into an anime first came to you, Chief Director Omori?

Yes. Originally, Studio Shuka’s (“Brain Base” at the time) producer Yumi Sato expressed a strong desire to adapt the original work, so she reached out to the former producers at ANX [Aniplex], who immediately contacted Hakusensha. On that occasion, other companies that were already interested in the work, such as ADK [ADK Emotions Inc.], reportedly made a production proposal to the committee. She then reached out to me, since we had previously worked together on other projects, and that’s how I became involved in the anime adaptation.

At that time, though, I honestly thought that portraying the atmosphere and tone created by the original work would have been a very difficult task. Additionally, the manga had only just begun serialization at the time, and the author, Yuki Midorikawa-sensei, was still in the process of developing the story, so we were able to make adjustments to the roles of the characters and the timing of their appearances under her guidance.

—— There were some meticulous changes to the original work, then.

Initially, in the original work, the protagonist Natsume Takashi had a somewhat detached and mysterious air, but we slightly adjusted his character to make him a little more relatableーan ordinary boy who, due to the single fact that he can see ayakashi, ends up distanced from the people around him.

In the manga Takashi has silver hair, but giving him silver hair in the anime would have inevitably made him stand out visually, so we opted for a light brown hair color. Furthermore, to make the everyday drama easier to follow, we adjusted the story so that Takashi’s friends not only include Nishimura (Satoru) and Kitamoto (Atsushi), but also Sasada (Jun), the only main female friend, who we decided would no longer transfer out [In the original work, Sasada transfers schools, but in the anime, she appears as one of Takashi’s classmates].

—— I imagine you had quite a few detailed exchanges with Midorikawa Yuki-sensei, what were your impressions from those conversations?

First of all, she struck me as a very kind and thoughtful person. The first time I met her was at the initial greeting with the art direction department, the characters and yokai designers, and all of the main staff. On that occasion, I asked her various question about the work, and I remember being struck by how sincerely she answered each one. She was so enthusiastic in answering our questions that I heard she came down with a fever [the term used here is 知恵熱 (chie-netsu), literally “wisdom fever”, which colloquially means “a fever that comes from using one’s head too much” t.n.] the day after meeting with us (laughs).

Not only did I get the impression of her kindness from our face-to-face meeting, but I also felt that the good qualities of her personality shined through in Natsume Yuujinchou, the work itself. What I especially realized after starting the anime production and working on the storyboards for each episode was that Yuki Midorikawa-sensei has a strong desire to “entertain the readers”.

She often adds little playful touches throughout the work, incorporates unexpected and interesting twists into the story structure, and includes elements designed to entertain the readers. I feel that she’s very in tune with her readers.

—— It is said that the model for Natsume Yuujinchou’s setting is Hitoyoshi-shi in the Kumamoto prefecture. I’ve heard that you went location scouting in Hitoyoshi too, Chief Director Omori.

Since my debut as a director, I’ve never missed a single location scouting. The purposes of location scouting is not only to see the actual locations where the work will be set, but also to walk the site together with the staff, including the art director, and have discussions to develop a shared understanding of the vision behind the work.

Of course, there are times like with Durarara!! [“デュラララ!!”, 2010, another TV anime series directed by Omori] where the landscape and spatial relationships are portrayed exactly as they are in real life, but that’s not the case for Natsume Yuujinchou, where we’re just using the overall atmosphere of Hitoyoshi in Kumamoto.

—— I wonder what kind of town Hitoyoshi-shi is. How are the townscape and scenery of Hitoyoshi reflected into the anime?

One thing that I clearly remember is the kindness of the people who live there. Especially, when you cross paths with middle-school or high-school students, they always greet you. When I asked Midorikawa-sensei about it, she explained that Hitoyoshi, due to its geographical location in a basin, has historically been a region wary of invasions from surrounding forces.

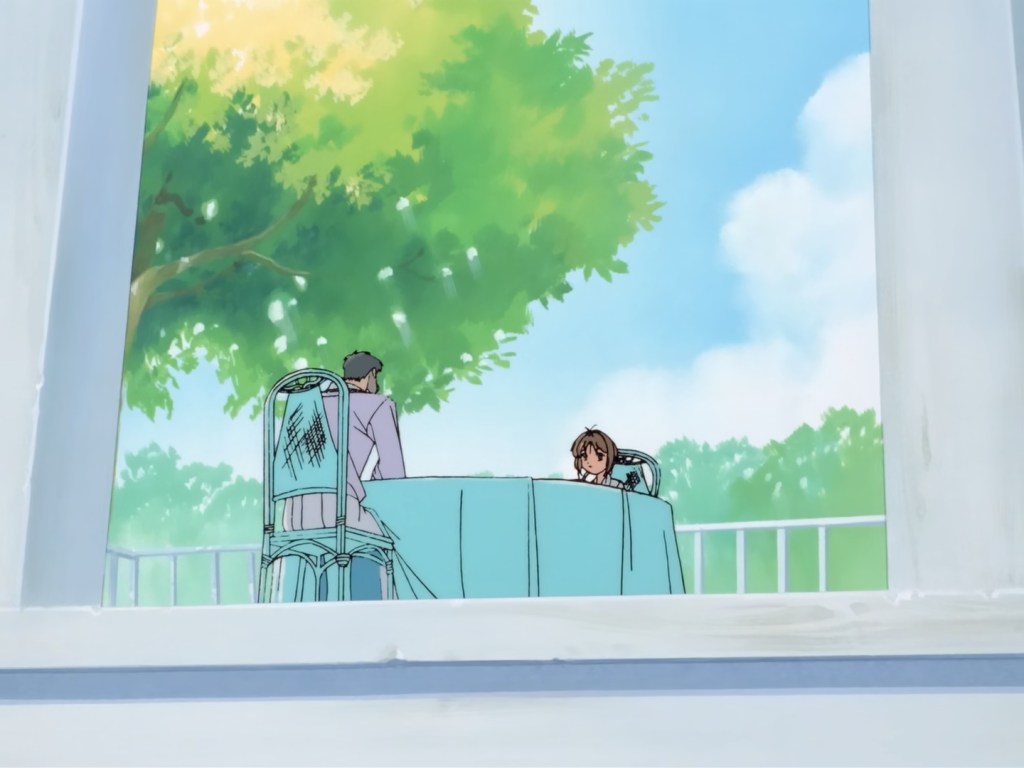

That’s why the courtesy of greeting someone they’ve never met before as a way of confirming what kind of person the other is has become a local tradition. I thought, “I see, so those greetings also hold that meaning”, but still, it’s always nice to be greeted with a smile by middle and high school students, isn’t it? (laughs). Also, perhaps for the same reason of being cautious of their surroundings, the fences around the houses are quite low.

—— The fences are low?

Exactly. The fences around the houses in Tokyo are approximately 170cm to 180cm tall [about 5’7” to 5’11”], and you can’t quite look inside even if you stretch, whereas the fences in Hitoyoshi are about chest-height, allowing you to see the surroundings over them. Rather than making them taller to prevent intrusions, the low fences, like the greetings, allow for assessing the surroundings for self-defense, and that custom has been deeply rooted to this day. These are some of the elements we’ve carefully preserved in the art direction of Natsume Yuujinchou.

~ Portraying the world of Natsume Yuujinchou in a captivating way through visuals and sounds ~

—— When creating the anime, what aspects of the original did you focus on the most?

In every chapter of the manga, Takashi’s monologues are used in a very impactful way. That particular way of using them was one of those aspects. Takashi’s monologues have two layers to them: one is used to express the emotions of the other characters, while the other is a separate, more subtle monologue that occasionally emerges to convey his own personal feelings.

However, when trying to combine the two types of monologues into a single prose, the meaning becomes disconnected. So, we arranged the monologues and structured the dialogue (script) by choosing which of the two types to use.

The one type we don’t convey through the actual dialogue, we depict with the drawings. One type is conveyed thought the words, and the other through the character’s expressionsーa quality unique and inherent to the visuals.

Additionally, we have to decide whether the monologue should be delivered in a more narrative style or a more emotional tone. For that, we arbitrarily choose one of the two when writing the script, then I consult with Natsume Takashi’s voice actor, Kamiya Hiroshi-san at the recordings whether a more narrational and firm tone or something in-between works best, and thoroughly adjust the balance as we record.

—— Chief Director Omori, you not only worked as the director for the Natsume Yuujinchou series, but also took on the role of sound director. The free and unrestricted acting of the members of the cast is as well one of Natsume Yuujinchou’s most charming aspects. In the conversation scenes with the mid-rank yokai, the so-called “Dog’s Circle”, there are often fun exchanges, including puns and ad-libs, which create very pleasant and enjoyable dialogues.

I mostly leave the recording of the Dog’s Circle scenes up to the cast. At first, I used to reject their ideas because I didn’t understand the puns they made (laughs). Nowadays, Matsuyama Takashi-san, the one-eyed mid-rank yokai’s voice actor, basically acts as the leader on set, he preps the manuscript (the ad-lib lines) for the Dog’s Circle scenes, coordinating with the cast outside the studio before the recordings. This kind of fun and collaborative recording sessions are one of the unique charms of working on Natsume Yuujinchou.

~ The development and growth of the protagonist Natsume Takashi and the yokai Nyanko–Sensei ~

—— The protagonist, Natsume Takashi, is a boy who, unlike ordinary people, has the ability to see ayakashi and hear their voices. Having depicted him since Season 1, do you feel his character has shown any development or growth?

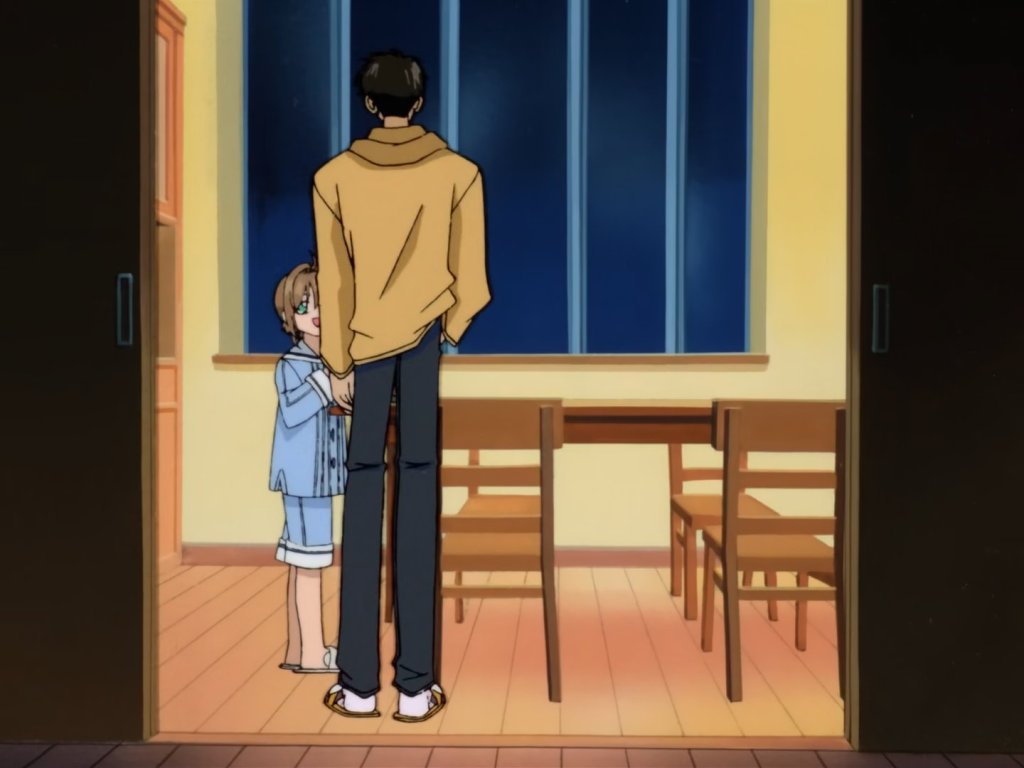

In both Season 1 and 7, he’s got his friends by his side and not much has changed around him. However, what has changed is how much he has opened his heart to those friends.

In the beginning, he probably acted more reserved, with a guarded manner that subtly signaled that he couldn’t fully trust others. Over time, he gradually got used to his friends, and now, even when minor issues come up, he can brush them off with a joke. I feel he’s developed a certain warmth or ease that wasn’t there before.

His feelings towards the ayakashi have seen some developments too; as of now (Season 7), I believe that his ayakashi and human friends have both become fairly closer to Takashi’s heart. He still retains a sense of caution and tension when interacting with the exorcist clans, but he’s gradually become more emotionally open.

Especially with Matoba (Seiji, the young head of the Matoba exorcist clan), Takashi’s starting to show a calmer, more thoughtful side as he works to understand him, which I believe is a sign that reflects his growth. I think this seventh season is series that shows the unexpected sides of all the characters, so it’s not just about Takashi’s growth. I hope the viewers will enjoy how the way the other characters are perceived evolves as well.

—— Takashi has spent a lot of time together with his yokai partner Nyanko-Sensei as well, and their relationship feels like a bond of fate. Nyanko-Sensei’s true identity is the high-rank yokai Madara, and he acts as Takashi’s partner on the condition that once the boy dies, he will inherit the Yuujinchou (the Book of Friends), but Nyanko-Sensei has changed and grown too.

I think Nyanko-Sensei has changed a lot as well. Probably, it’s the presence of Takashi that has softened him. Actually, in Season 7, after a long time he declares once again his goal to inherit the Yuujinchou upon Takashi’s death, however, their relationship has evolved to the point where it feels natural, as if he has forgotten about that initial promise. It almost feels like his objective has become nothing more than a jest. In a certain sense, it’s a positive relationship.

—— What kind of difficulties and appeal does depicting the characters’ growth present for you, Chief Director Omori?

I originally started working in the field of visual production exactly because I wanted to depict the movements of people’s hearts, the changes in their expressions, and the shifts in their demeanor. Not just in Natsume Yuujinchou, I really enjoy portraying the growth and evolution of the characters in every work. I believe that carefully portraying the movements of people’s hearts is the true charm of this work.

Part ②

In this second part of the interview, director and chief director,Takahiro Omori shares his thoughts on the anime production process, particularly in the context of digital technology’s rise over the past 16 years, focusing on what has and has not changed in the production of Natsume Yuujinchou.

※ this interview was conducted on September 11, 2024.

~ The unforgettable episodes from the past 16 years ~

—— It’s been 16 years since you started working on the Natsume Yuujinchou anime series. Are there any episodes in particular that left a lasting impression on you, Chief Director Omori?

Last year, during the “Revacomme!! × TV Anime Natsume Yuujinchou Anime Adaptation 15th Anniversary” event [December 2, 2023] fan-voted popular episodes were selected.

Among the episodes that were ranked highly in the fan vote, there were some where the protagonist, Natsume Takashi, and Nyanko-Sensei weren’t the main focus [the top-ranked episode in the fan poll was Episode 10 of Season 5, titled “Toko and Shigeru,” and the third-ranked episode was Episode 4 of Season 3, “Young Days”]. I thought that the fans attending the event chose the episodes they were particularly passionate about, but as the director, I was still surprised.

—— I understand that the fans who attended the event must have had a strong passion for the series, so, albeit surprising, those results make sense. There are many fans who prefer secondary characters over Takashi and Nyanko-Sensei, which, if anything, proves that the series is beloved in every facet.

I feel this every time there’s an event, but Natsume Yuujinchou fans are really devoted and trustworthy—every time I revealed something and asked them to keep it to themselves, they’ve never broken their promise and kept everything under wraps. I’m really grateful that highly literate and strongly passionate fans gather for these events.

Furthermore, their deep understanding of the work is impressive. From the creator perspective, it’s something I’m truly grateful for, because even when the direction and presentation are subtle or between the lines, I always get the feeling that my intention is clearly understood.

—— Throughout the series, there have been a few anime original episodes, right?

Initially, the original manga had just started serialization, so there weren’t enough chapters to adapt into the anime, therefore we decided to add a few original episodes. What I’m most grateful for is that the original author Midoikawa Yuki-sensei herself wanted the anime to include original episodes. “I’d like you to play around and have fun with these characters”, “I’m excited to see what you will do!”, she kept supporting us as a fan of the anime version.

—— Hearing “I’m exited” from the original author must be the the highest form of praise an anime creator could possibly receive.

You’re exactly right. Midorikawa-sensei has always been a tremendous supporter of the Natsume Yuujinchou anime, to the point she set up her social media account and kindly reposts all the content related to the anime.

—— When creating the original episodes, I wonder what kind of exchanges you had with Midorikawa-sensei.

I’ve written the scenario for the Natsume Yuujinchou Drama CD as well, and generally, during these occasions, I always have very detailed discussions with Midorikawa-sensei while writing the screenplay. I propose a basic idea and concept for the episode, and Midorikawa-sensei accepts it. Then, we discuss aspects like “what would this character say in this situation?“ or “perhaps this phrasing would work better?”. Through these exchanges, I always receive valuable input and ideas.

~ We are able to achieve this because the staff remained unchanged ~

—— I believe the fact that during these 16 years of Natsume Yuujinchou the staff hasn’t practically changed at all is another distinctive trait of the series. What are your feelings in this regard?

Having worked together for such a long time, there’s a clear advantage in that the staff shares the same vision and goals for the series. Without the need for words, we all share the common understanding of where the line between acceptable expression and something that would detract from the original work’s world-view is. I think this shared insight is a strength of the team.

On top of that, everyone in the team has a well-established grasp of each character, so it’s also a key strength that many different ideas can come forward. I believe the individual ideas each person brings add a unique touch and accent to the project.

—— So, with the production team’s long-term involvement in the project, they’ve come to know the series deeply and thoroughly, making it possible to create an even better work.

We’ve been doing this for seven seasons, so the staff at Studio Shuka has become stronger and more reliable, to the point we can now focus the production around in-house team members. As we’ve worked together on the series over time, we naturally developed these qualities and strengths.

~ What the veteran staff working on Season 7 hold dear ~

—— Omori-san, you’re the chief director of Season 7, while Ito Hideki-san, who directed the movie Natsume Yuujinchou: Ishi Okoshi to Ayashiki Raihousha [“夏目友人帳石起こしと怪しき来訪者”,“Natsume’s Book of Friends: The Waking Rock and the Strange Visitor”, 2021], is the new director.

Ito-san is a person with a very soft touch, capable of creating really tender visuals. I took a step back and observed from a distance, so while Director Ito, who fully immersed himself in the work, might have had some difficulties, I believe that this time, all of his qualities and gentle touches have really come through.

—— As for the other main staff, it’s still the usual lineup. Composer (Makoto) Yoshimori-san has been creating heartfelt and touching pieces since Season 1, what do you think is his and his music’s main appeal?

Up until now, Yoshimori-san has crafted around 120 musical tracks for Natsume Yuujinchou. I’ve been asking him to compose the music for other works even before this series. The first time we worked closely together on a main project was for the anime Gakuen Alice [“学園アリス”, “Alice Academy”, 2004] but before that, we were just drinking buddies.

Yoshimori-san’s understanding of the original works is incredibly profound, isn’t it? Of course, for each season, I create a music request sheet outlining the overall concept and my vision, and then I ask Yoshimori-san to compose new pieces accordingly, but he always says that the titles of the tracks and the approximate desired length are all he needs to come up with the score. I believe he’s capable of doing that because he thoroughly reads the original work in advance.

Sometimes, he gets so carried away that the resulting music can’t be used in the anime (laughs). However, I truly appreciate that he never loses his spirit of adventure and continues to experiment with music for the series. Recently, he said “I’m fine with however you use the music I’ve composed in the visuals, I’ll leave it all to you”.

—— Art Director Shibutani Yukihiro-san too has been part of the staff since the first season.

When this series began, the whole anime industry was transitioning from the analogue production environment to the digital one, and, at the time, the resolution of the visuals hadn’t been precisely set yet [the full transition to digital terrestrial broadcasting was completed in July 2011].

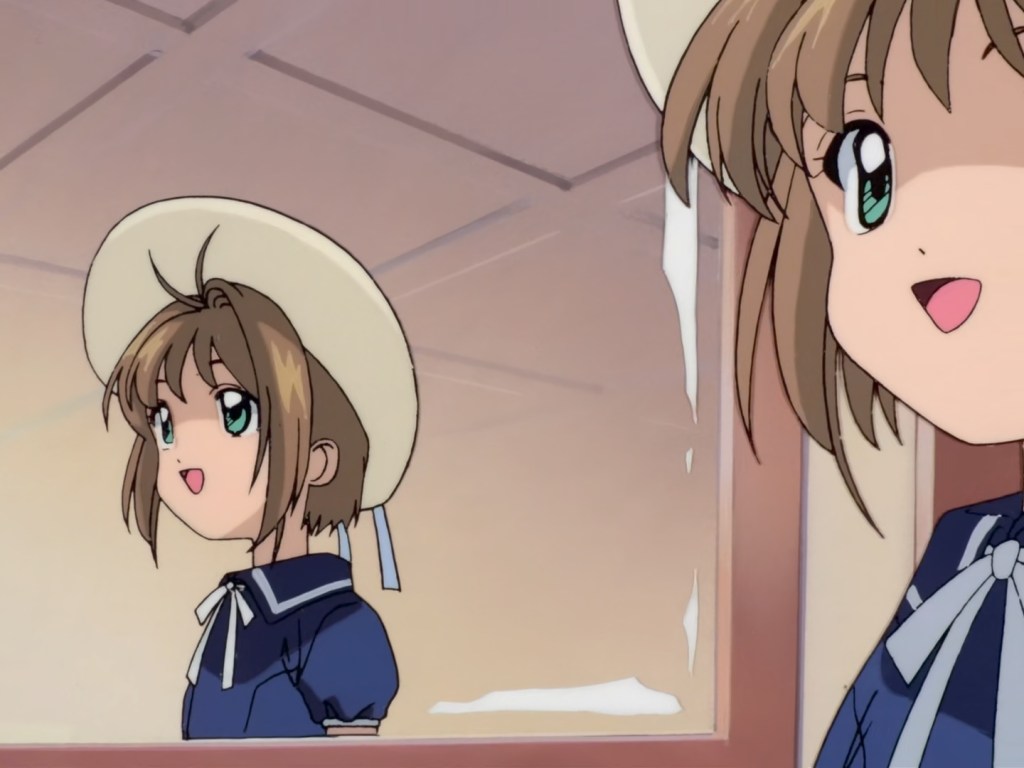

As the digitalization advanced, Shibutani-san continued to prefer the texture of real paper. Even as the staff transitioned to digital animation tools, Shibutani-san has consistently worked with watercolors to create his artworks. The final clean-up is done digitally, but he places great importance on the watercolor touches.

From Season 6 onwards, the Art Director (Mao) Miyake-san has joined the team and while successfully expanding the artistic scope of the series, she still maintained the original aesthetic. While I’m getting a lot of inspiration from the two of them, we continue to create new artworks by referring to past works, often asking questions like “what did the sunset look like in that episode?” or “what was the special setting in that moment?”.

—— You mentioned how the anime production environment has changed during the past 16 years, but did that transition have any impact on Natsume Yuujinchou?

It’s not like it was a sudden change or anything. The things that we originally used to draw on paper, we brought over to the digital supports, maintaining the same touch and style, which I personally prefer as well. So, whether it’s digital or paper, I don’t think the quality of the work has changed.

However, one thing that became particularly noticeable during the production of Season 7 is that, with the increase in digital douga [in-between animation], the thinness of the lines started to change. Back when we were drawing with paper and pencil, there were limitations inherent to that medium; no matter how thin we tried to make the lines, at some point they just couldn’t get any thinner.

But with digital animation, you can make them so thin they’re barely even noticeable. There are some instances in the douga where the lines are thinner than necessary. The characters in Natsume Yuujinchou have simple designs, so I think it’s better to make the strokes a bit thicker to emphasize the variation in the line-art. I value the expressive power lines have, and if they become too thin, no matter how carefully made the douga is, it becomes difficult to approve and utilize.

—— So the gentle yet delicate tone of the anime Natsume Yuujinchou is expressed through the variation in the lines.

Another thing that changed with the shift to digital is the number of color options available for selection, which has expanded enormously. I believe it was also very important to figure out how to maintain a color palette that still captured the essence of Natsume Yuujinchou.

~ Season 7 and the future of the Natsume Yuujinchou anime ~

—— Season 7 is finally about to air. What would you like people to pay attention to in this series, Chief Director Omori?

To be honest, I believe the sixth season ended in a way that left some mysteries unresolved, or rather, with a bit of an unsatisfying conclusion. We made it that way because we thought we could start working on Season 7 right after the end of Season 6, but unfortunately it took way longer than we planned, and I feel incredibly sorry for all the fans. That’s why, this time, I’m sincerely glad we were able to complete everything without troubles.

—— Your involvement with the series has become quite long. I believe Natsume Yuujinchou will continue after this season, but do you have any goals for the future?

It’s the work I’ve been involved with for the longest time in my career, and we were able to continue Natsume Yuujinchou alongside the manga up until now. Talking about the future, when the original work eventually comes to its conclusion, I hope to give the to anime as well a proper ending that satisfies the fans.

—— Over the 16 years of its history, I believe the number of fans watching Natsume Yuujinchou has increased, and I’m sure they’re all looking forward to the future developments.

By taking part in the events, I realized that among the fans there are some who watch it along with their families. Since it’s not a work made with the influence of current trends, I’m glad it has become something people still enjoy after all this time. It’s an easy-to-watch series regardless of which episode you start with, and I would be happy if people continue to enjoy it in the future.