It’s 2014, I’m a middle-school student and on my journey getting into anime I stumble across KyoAni‘s adaptation of Hyouka. Aside from its contents, which I’m still deeply attached to to this day, it’s exactly this show that years later (that is, a few years ago) got me interested in the production of Japanese animation as a whole, or to put it into the right, narrower context, in the “technical” aspects of it, such as storyboarding or direction. Hyouka being a masterclass example of both these things certainly helped, but who I really need to thank for getting me into this world of carefully designed visual exposition, is one of the creators whose content has taught me the most and has changed the way I engage with anime altogether: Replay Value. Specifically, with his Hyouka breakdown series, A Rose-Colored Dissection (which, of course, I encourage everyone who still hasn’t to check out).

Given how influential of a work it’s been for me, I’ve been thinking of writing a series of posts about Hyouka ever since before getting started with this blog, but for now it’s gonna remain an idea, as I think it would end up being just a (probably worse in exposition) repetition of what Replay Value has already done on his hand.

Instead, what I’ll be doing today, trying to retain a semblance of consistency with the format I’ve already used with Kusuriya no Hitorigoto a few seasons back, is a commentary of the new anime series produced by studio Lapin Track, directed by Mamoru Kanbe, Shoushimin Series (localized as “SHOSHIMIN: How to Become Ordinary“).

Why the preamble on Hyouka then? Well, aside from my desire to address the biggest inspirations that led me to do what I’m doing, Shoushimin too is an adaptation of a novel by the pen of Honobu Yonezawa, and although I initially didn’t want to compare it to Hyouka, afraid that making such a connection would feel somewhat forced due to my (heavily) biased attachment to the latter, one episode was enough to hit me with a wave of nostalgia thanks to the intrinsic qualities unavoidably inscribed in its writing, that I couldn’t help but bringing it up anyways. What I was not expecting to see though, were the same idiosyncratic visual quirks (albeit in a different capacity) that made me fall in love with Hyouka (and by extension, animation) years ago.

To be clear, I’m not implying nor meaning to say that the direction of Shoushimin Series has been influenced by Hyouka‘s, nor that they’re trying to replicate it in any way (in fact, I’d argue the two approaches don’t really have all that much in common). Instead, what I meant to say is that Shoushimin too is filled with expedients of visual storytelling, be it via clever framing or a descriptive use of light, that make for a perfect subject for my blogposts.

Well then, here I am, ready to bother you, dear reader, with my inconsistent ramblings about what I can already tell will be one of my favorite media experiences of the year, the Shoushimin Series anime adaptation.

Episode 1 – 羊の着ぐるみ: Sheep Costume

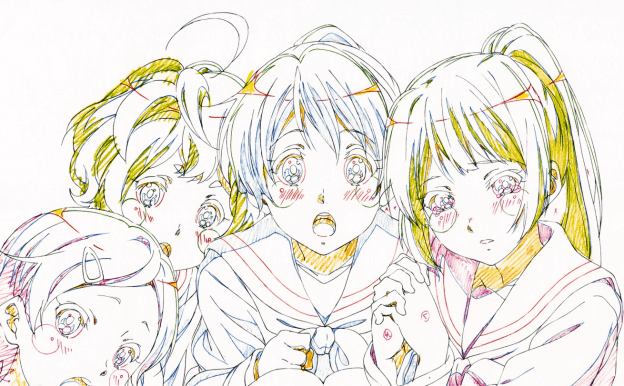

Right off the bat, I’d like to address some general “visual qualities” and features I noticed, like how, with good and refined drawings, the (purposefully) rather simple and malleable character designs by Atsushi Saito were delivered in a very expressive way, well capable of conveying the broad range of emotions exhibited in this premiere. (Literally) on top of that, the compositing also did a fairly good job at integrating the digital “cels” with the realistic backgrounds, making at times use of additional effects to render the scenes in a more true-to-life fashion (like blurring out the objects that are closer to the camera), or more deliberately, to convey a sense of “isolation” or “separation”, like with the fully blurred background in this shot. The color design in general, opting for a properly muted palette, also helped in setting the tone of this story, suggesting on his hand too the overall focus on the mundane.

Another visual feature, albeit not descriptive of the contents of the show, that’s pretty much impossible not to notice since the very beginning of the episode (including the visuals for the opening!) is the 21:9 aspect ratio, as opposed to the nowadays standard 16:9. It’s by no means an “unprecedented feature” in anime or anything on that level, though, it’s still pretty nice to see a TV show almost fully (as the ending visuals will go back to the now-traditional 16:9) committing to it.

Another aspect worth of mention, this time not related to the visuals, is the sound design. With the focus mainly set on reproducing accurate background and ambient noises, the degree of immersion this episode was able to achieve was rather high. This is to say, the well-designed sound effects and the softness (or in some instances, lack) of the soundtrack really helped making the depiction of the world, and the interactions the characters have with it, feel more concrete and grounded in reality.

The main highlights for me were of course the many instances of visual storytelling present throughout the episode, which, by extension, I’d say suggest a broader approach to the direction of this show as a whole.

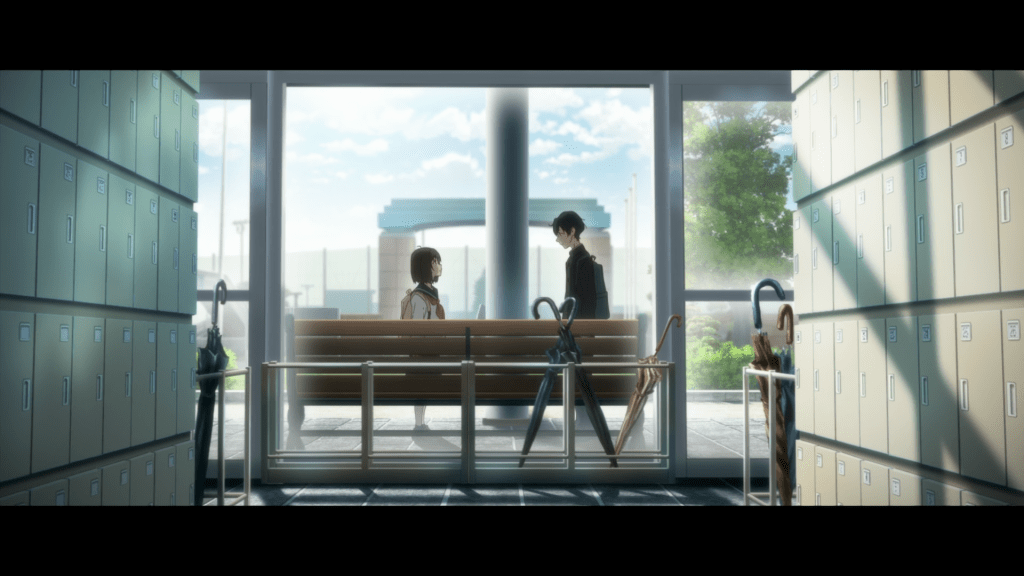

A lot can be inferred solely from a visual standpoint on the relationship between the two main characters, Osanai and Kobato. The way they’re often laid out, being parallel to each other in a frame whose space is equally divided by some element in the background or foreground (like in frames 1 and 2), implies some sort of contrast between the two, but not in a dichotomic way, rather, in a symmetrical one. As the episode makes clear in its later phases, the two of them are bond together by their mutually shared dream of “becoming ordinary”, which manifests in different but cohesive ways; they strive for the same goal, but they do have their own preferences and identity (for instance, Kobato not being fond of sweet food contrary to the gluttonous Osanai, a characteristic noticeably showcased by the striking difference in their orders in frame 1), which ultimately result in a different approach towards their objective. In other words, their symmetry implies complementarity, not contrast, to one another.

It’s when such visual equality is missing (like in frame 3) that the implications change, and the meaning shifts to another layer, like depicting the difference between being “in the light” or “in the dark” about the solution to a certain hazy case.

Another type of clever framing and layout at play in this episode, certainly is one that implies actual “disconnection” or “distinction” (as in the case of frames 4 and 5). Uneven spacing and positioning in the frame, in addition to a feeling of unease and tension, convey a clear sense of distance that serves to delineate the sharp separation between the two parties, as well as the cohesion of one of them (namely, Kobato and Osanai).

What to me captured the eccentricity of this show’s direction the most, was undoubtedly this whole sequence (which the video above shows just the last portion of), basically, the “unraveling the mystery” sequence. While Kobato is explaining his theory for what had actually happened to Osanai, as the two walk home after having reached a conclusion with the interested party (the “thief”, Takada), we’re shown a visualization of Kobato‘s thought process with him “physically” retracing the culprit’s movements and actions. The sequence then ends with the portion attached above, that is, a compilation of disconnected cuts showcasing the two main characters talking, ultimately stating their will and promise to live as “ordinary people”, and making a little detour to the river on their way home. This a-spatial and a-chronological visual presentation effectively succeeds in feeling immersive and compelling, and in a sense prompts the viewer to actively engage with the scene, rather than experiencing it passively.

I’m calling it a “distinct trait of the direction” because as we’ll see in a moment, the very same peculiar approach is present in the second episode as well, and moreover, this way of presenting the story and the characters’ interactions is totally original to the anime (as one could probably correctly guess), and no trace of this “disconnected” exposition is present in the source novel (which, by the way, I couldn’t help but start reading).

Before jumping into episode 2, I’d like to mention how clever and, more importantly, well-realized of an idea the ending visuals are. Basically, what we’re looking at is a series of live-action photos (albeit with some touch-ups) which the hand-drawn characters move in and interact with, as to once again convey how grounded in reality this whole setting is. On top of looking very nice, I believe it’s neat how every (visual and not) aspect of this show serves a purpose in realizing the well-defined vision behind this adaptation.

Episode 2 – おいしいココアの作り方: How to Make Delicious Hot Cocoa

Starting off in the strongest possible way to maintain the sense of realism established in the first episode, episode 2’s introduction takes place in a beautifully crowded shopping gallery, where the incredible lighting and (again) the very well-designed background sounds really make the already immersive setting feel as grounded in reality as it can possibly be. So grounded that in fact, following the steps of the previous episode, the locations where the events unfold are actually real places.

Some other of the aforementioned visual qualities have also naturally been brought over to this episode too, like the super pretty drawings once again putting to good use the ductile character designs, and the wide spectrum of emotions properly portrayed on the characters’ faces (and notably, the narrower aspect ratio is of course still here as well!).

What I’m most happy to see again though, is obviously the same approach to express and convey in a visual way. In contrast to the first episode, it’s not background elements that draw lines between the characters, rather, this time, the background as a whole and its layout become means to define the boundaries between them.

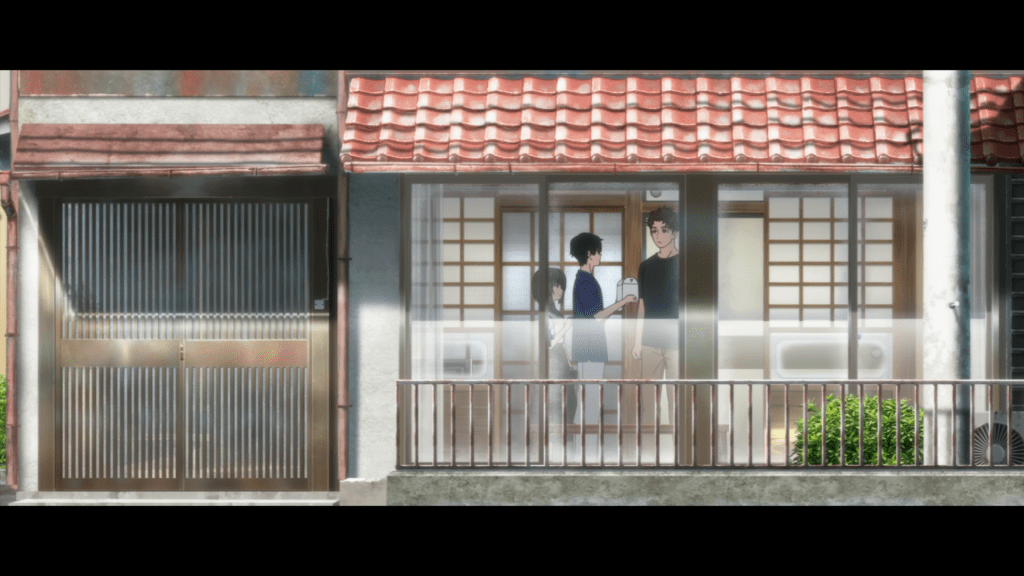

It’s especially clear that Osanai kind of feels out of place visiting Kengo‘s, Kobato‘s friend, home. Frames 1 and 2 intelligibly hint at that, “encapsulating” the characters inside pre-defined portions of the background, and while Kobato and Kengo fit in the same space, Osanai is the only one that’s not entirely enclosed within the same physical limits. She’s also almost forcibly brought into that same space by Kobato, abruptly so (as the quick shift from the more far away to the really close-up view strongly suggest) with him taking the box with the cakes straight from her hands and offering it to Kengo.

As the two friends begin to talk, it’s quite noticeable how in frame 2, compared to frame 1, Osanai is growing more and more distant from the two; whereas in frame 1, just a small portion of her figure didn’t fit in the same area as Kobato and Kengo, now it’s only that very small portion that’s able to fit in, while the almost entirety of her body finds itself to be out of that boundary. Moreover, not only she’s practically in a different space than the two, she’s also nearly fully covered by the sliding door, as to indicate she’s more of a background presence than a foreground one in the scene.

The frame that does the best job at conveying the character’s “affiliations” with one another, and by extension their division, is definitely frame 3. Not only Kobato and Kengo are again the only ones to fit into the same space together (in this case, the reflection on the mirror) with Osanai being the one that’s now totally left out of it, purposefully placed in the farthest right corner of the frame, but the layout also suggests a broader outline on how the characters are grouped together. Dividing the frame in two sections, the inside the mirror and the outside of it, Kobato is able to fit in both at the same time, with his upper half in one and with his lower half in the other, designing him as the “common ground” between the characters; the mirror reflection contains Kengo but not Osanai, and the outer portion of the room contains Osanai but not Kengo, and Kobato is part of both.

The visual themes of “separation” and “division” are again extensively present throughout the episode, although in a formally different flavor, one that’s nonetheless still able to retain the same level of expressiveness and clarity.

As expected (and not only because I’ve hinted at it earlier), when the characters are putting their efforts into solving the (extremely mundane and unimportant) mystery, the presentation heavily relies on spatial and chronological dislocation, once again also exhibiting their thought processes and theories as a visualization of them actually acting as the culprit.

There’s something so beautifully dissonant in the sudden changes in location and time, especially as they happen without interrupting the flow of the dialogue, almost as if the “outside” is sort of a private, ethereal space, solely dedicated to the more introspective moments inside one’s mind. As they delve deeper into their abstractions and thoughts, they’re transported in another dimension altogether. The characters being in the same headspace is no more just a figurative image, instead, it manifests almost as a physical phenomenon.

I certainly can’t say I’ve experienced other visual presentations of the same concept as eccentric and compelling as this one.

Another aspect of this episode I cannot possibly fail to mention, is the overall focus on body language and mannerism, depicted with such an utterly great accuracy that it truly feels real and heartfelt. The cut above is of course not the sole instance of that, many more examples, including Kengo‘s nervousness to introduce the uneasy topic of the conversation he wants to hold, and Kobato intimately sliding his finger on the border of his cup, are featured here and there all through the episode. Yet another quirk to make this world and characters feel vivid and real.

Lastly, a noteworthy element is the incredibly solid attention to detail when it comes to physical interactions with objects. It’s not every anime’s feat to make you feel the density of every single layer of a piece of cake as a character’s tries to cut through it. And not only that, incredibly accurate fluid animation seems to also be a given throughout this episode.

It all makes perfect sense though, since the main topic of episode 2, as the title doesn’t try to hide in the slightest, is the not-so-secret preparation of a delicious cup of hot cocoa.

Hopefully, I was able to convey in this post even just a tiny bit of all my enthusiasm towards this new series, in addition to providing some maybe-interesting insights about its presentation. I was really anticipating Shoushimin since the day it was announced, but I would have never guessed it would hook me to this extent. It truly encapsulates everything I love about animation as a medium, and having a place (that is, this blog) to extensively talk about it really feels like a blessing to me.

Needless to say, I can’t wait for the next episodes to come out, and I’m sure they too will be filled with cool and neat stuff, well worthy of being written about.